Cross-border transactions involving services include the movement of either the producer, the consumer, or capital for investment purposes. The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) defines cross-border trade in services using four modes of supply: Mode 1 involves the flow of services from one country’s territory to the trade partner’s territory; Mode 2 consists of the collection of services from one country to consumers from another country; Mode 3 involves services provided by a service supplier of one country in the territory of another country, including through ownership or subsidiaries; and Mode 4 involves services provided by a service supplier of one country through the presence of natural persons in the territory of another country. Modes 1 and 2 could reflect the free flow of goods, Mode 3 represents the free flow of investment, and Mode 4 reflects the free flow of people. Hence, the free flow of people can be linked to the free flow of goods and investment.

Recent technological advancements have facilitated cross-border transactions through the digital trade of goods and services. This type of trade encompasses all digitally ordered and delivered goods and services. The study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organization (OECD, IMF, and WTO 2020) defines digitally delivered trade as international transactions electronically delivered remotely through computer networks, including insurance and financial services, professional services, sales and marketing, research and development, and education services (UNCTAD 2022). On the other hand, digitally ordered trade refers to international purchases and sales of goods or services through computer networks designed for this purpose, similar to e-commerce. The data movement across borders is thus an essential element in the growth of service supply models, as well as production networks (González 2019). Data also links firms and consumers globally, facilitating the management of global production networks and business-to-business transactions within them and transactions between consumers or businesses purchasing from each other through online platforms (OECD 2019).

The digital economy plays a crucial role in the international trade of the ASEAN member states, particularly for their micro, medium, and small-sized enterprises (MSMEs). The ASEAN digital economy is rapidly growing, with the market size expected to exceed $360 billion by 2025 and grow to $1 trillion by 2030 due to the growth in e-commerce, digital financial services, and food delivery (Google, Temasek, and Bain & Company 2022). The digital platform business alone has created 160,000 direct jobs and an additional 30 million indirect jobs. The e-commerce industry thrives, with 20–25 million unique merchants operating across marketplaces, direct-to-consumer, and grocery platforms, according to e-Conomy SEA 2023.

Digitalization offers new opportunities for MSMEs to expand their business and increase productivity by using digital tools and technologies to reduce production costs. According to a survey conducted by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and Google (2022), 80% of MSMEs in ASEAN have increased their use of digital tools in 2020–2021, indicating these businesses’ growing adoption of digital tools and technologies. This shift toward digitalization presents new opportunities for MSMEs in the region to reduce production costs, enhance business productivity, and expand their international reach. The adoption of digitalization by MSMEs is significant for their internationalization process, as increased international exposure has been linked to higher wages and increased job creation for productive firms (Wagner 2012). By lowering trade costs and connecting supply and demand through digital platforms, MSMEs can overcome constraints associated with exporting and tap into new markets (González 2019).

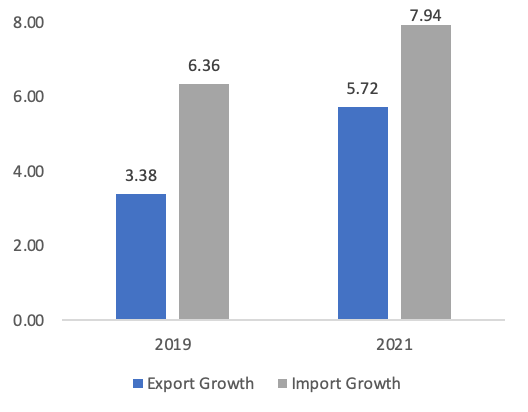

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in digital use in ASEAN. Taking a sample of six member states (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Viet Nam), there was an increase in the average growth of export in digitally deliverable services from 3.38% in 2019 to 5.72% in 2021 (Figure A7.1 in the Appendix), exhibiting positive growth of digital trade in services particularly post-pandemic and indicating the utilization of electronic trade administration documents. Using data from Google, Temasek, and Bain & Company (2022), the six ASEAN member states have made notable recent progress in developing a digital economy. For example, the aggregate gross merchandise values of the digital economy in these countries have jumped significantly, from $102 billion in 2019 to $194 billion in 2022 (Figure A7.2). This fact indicates that countries have progressed in establishing and maintaining their domestic electronic transactions framework. Moreover, it suggests establishing digital identity and authentication systems and e-invoicing for local transactions (Tong, Li, and Kong 2021).

Those movements toward digitalization might become one of the main strengths of the digital economy to expand business within local markets in ASEAN member states, including for micro and small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). According to the World Economic Forum Survey (2021), most MSME owners wanted to further digitalize their lives, indicating that digitalization would likely accelerate. Most (74%) MSME owners in ASEAN have implemented digitalization for more than half of their tasks. This fact indicates the influence of digitalization, as those who have already acquired a satisfactory level of competence and benefitted from its advantages are now motivated further to enhance their digitalization efforts (WEF 2021). Another aspect that could strengthen the digital economy and cross-border transactions is government provision to promote access and inclusion of information technologies for the people, measured by the E-government Development Index. While the overall index of the six ASEAN member states ranges from middle inclusivity to very high inclusivity, human capacity shows a promising potential with an index ranging from high to very high inclusivity, as shown in Figure 1.

The opportunity for cross-border transactions using digital trade could be encouraged by at least three main features. First is from the demand side, where there was an increasing trend in the use of digital technology. For instance, there was a rising trend in internet connectedness that allows people to access online products and services (World Bank 2019), the number of social media users with a regional social media penetration at 63.7% (Statista 2023), and consumer spending on online time that reach ten hours a day in average (Google, Temasek, and Bain & Company 2019). These trends could encourage Southeast Asian businesses to innovate, adopt new technologies, and sell online (Hoppe, May, and Lin 2018), and more MSMEs might be favored by the low-cost, mass form of advertising that can influence consumers with product research and brand engagement. On the supply side, the infrastructure of information and communications technology (ICT) also supports the emerging use of digital technology for cross-border transactions. As indicated by Table 1, the Telecommunication Infrastructure Index in the six ASEAN member states, for example, could be classified as high for Indonesia, Philippines, and Vietnam, and very high for Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand.

| Country | E-government Development Index | Online Services | Telecommunication Infrastructure Index | Human Capital Index | Overall Classification | |

| Singapore | 0.913 | 0.962 | 0.876 | 0.902 | Very high inclusivity | |

| Thailand | 0.766 | 0.776 | 0.734 | 0.788 | Very high inclusivity | |

| Malaysia | 0.774 | 0.763 | 0.795 | 0.765 | Very high inclusivity | |

| Brunei Darussalam | 0.727 | 0.587 | 0.837 | 0.757 | High inclusivity | |

| Indonesia | 0.716 | 0.764 | 0.640 | 0.744 | High inclusivity | |

| Viet Nam | 0.679 | 0.648 | 0.697 | 0.690 | High inclusivity | |

| Philippines | 0.652 | 0.630 | 0.564 | 0.763 | High inclusivity | |

| Cambodia | 0.506 | 0.418 | 0.561 | 0.538 | High inclusivity | |

| Myanmar | 0.499 | 0.307 | 0.608 | 0.583 | Middle inclusivity | |

| Lao PDR | 0.376 | 0.301 | 0.282 | 0.547 | Middle inclusivity | |

Second, the utilization of quick response (QR) payment for cross-border financial services within the ASEAN region presents an opportunity to enhance payment connectivity and support cross-border trade, investment, tourism, and other economic endeavors. The cross-border QR payment service enables the payment for goods and services across ASEAN member countries. Currently implemented in Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Cambodia, this service holds particular advantages for MSMEs by facilitating their engagement in international markets. Moreover, it caters to the needs of individuals such as tourists (Mode 2), business visitors (Mode 4), and those making purchases from overseas providers (Mode 1), who desire to make QR code-based payments for goods and services when abroad. This fact aligns with the demand for digital payment solutions expressed by three-quarters of MSME owners in the region (WEF 2021).

Third, the significant role of MSMEs in ASEAN presents another area of potential optimization. Southeast Asia alone houses a staggering 71 million MSMEs, accounting for 97% of all businesses in the region (Tan 2022). Despite their abundance, MSMEs in the region contribute an average of 40.5% to each country’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 19.2% to the total export value in 2020. This situation creates an opportunity for digital platforms to foster the growth of MSMEs by enhancing operational efficiency, expanding customer reach, and facilitating access to finance. Digital technologies have been suggested to streamline processes, support data-driven decision-making, and automate routine tasks, while the Internet has significantly reduced the costs associated with service delivery, marketing, ordering, and payment for MSMEs (Beschorner 2019; Tan 2022).

While the digital economy offers new opportunities for cross-border transactions among the ASEAN member states, it also raises considerable challenges for policy in a region where characteristics and regulatory differences between countries remain. The first challenge appears from the need for digital skills. Those with limited initial exposure to digital tools during the pandemic without appropriate digital skills did not experience the benefits of digitalization (WEF 2021). The digital skills and talent in ASEAN had the lowest score of 48.21 among the six pillars of the ASEAN digital integration index 2021, indicating a lack of a capable digital workforce risk is the most significant factor impeding digital integration and growth (ASEAN Secretariat 2021a). As a result, MSMEs have a high demand to improve digital literacy, provide digital skills training for MSME employees, and enhance the accessibility of quality internet and digital devices (WEF 2021). Nevertheless, the concentration of digital tool learners and teachers in big cities leaves small towns and rural areas at risk of being left behind in digitalization. It prevents the transfer of digital skills between generations.

Moreover, it is worth noting that the level of development in digital technology inclusivity in government and private sectors varies considerably across the ASEAN member states. This fact could be reflected by the e-government index and business-to-consumer (B2C) index. While Singapore (0.91), Malaysia (0.77), and Thailand (0.77) have very high e-government index values in 2022 (Table 1), the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) and Myanmar are still lagging with index values of 0.38 and 0.50, respectively. For the B2C index, shown in Table 2, Singapore (94.4) and Malaysia (81.3) are at the top of the list, while Cambodia (31.1) and Myanmar (24) are relatively far behind. Deficiencies hinder Indonesia’s B2C e-commerce in its logistics and payment systems, while Malaysia’s internet service quality is a limiting factor. On the other hand, Thailand benefits from strong logistics capabilities but encounters issues with the quality of its internet services (Lee 2021).

| Economy | Secure Internet Servers (normalized, 2019) | 2020 Index Value | Index Value Change (2019–20 data) |

| Singapore | 94 | 94.4 | -0.4 |

| Malaysia | 71 | 81.3 | -2.1 |

| Thailand | 59 | 76 | 2 |

| Viet Nam | 64 | 61.6 | 0.8 |

| Indonesia | 60 | 50.1 | 0 |

| Philippines | 39 | 44.7 | -5.1 |

| Lao PDR | 30 | 40.6 | 5.4 |

| Cambodia | 42 | 31.1 | 0.3 |

| Myanmar | 22 | 24 | -2.9 |

Additionally, there are disparities in the readiness of countries to adopt and utilize e-payment systems. These gaps primarily stem from variations in regulatory and policy frameworks and the availability of innovative products and services (Chen and Ruddy 2020). For example, the portion of the population in Cambodia, Indonesia, the Lao PDR, Myanmar, and the Philippines who made a digital in-store merchant payment using a mobile phone or made a digital merchant payment was still below 20% in 2021 (Table 3). This fact poses a challenge for the implementation of cross-border QR payment services. Another common challenge is that ASEAN member states are not all equally well equipped to deal with the privacy and security challenges that digital technologies can pose and have equal access to broadband networks as the essential infrastructure of the digital economy, resulting in lower adoption of these technologies, especially amongst MSMEs (Box and Lopez-Gonzalez 2017). MSMEs also face a more pronounced lack of familiarity with technological tools (ICC and Google 2022).

| Economy | Made or received a digital payment (%, age 15+) | Used a mobile phone or the internet to buy something online (%, age 15+) | Made a digital in-store merchant payment: using a mobile phone (%, age 15+) | Made a digital merchant payment (%, age 15+) |

| Cambodia | 26% | 4% | 1% | 3% |

| Indonesia | 37% | 18% | 6% | 13% |

| Lao PDR | 21% | 10% | 6% | 9% |

| Malaysia | 79% | 50% | 25% | 50% |

| Myanmar | 40% | 20% | 10% | 16% |

| Philippines | 43% | 36% | 12% | 18% |

| Singapore | 95% | 58% | 50% | 83% |

| Thailand | 92% | 51% | 57% | 63% |

| Viet Nam | 46% | 40% | 18% | 24% |

It is also important to note that the economic openness degree of ASEAN member states plays an important role in utilizing the digital economy, as the higher degree of economic openness for countries such as Singapore, Viet Nam, Malaysia, and Thailand indicates that digital trade is likely to be higher in these countries (Lee 2021). Therefore, the digital economy is at risk due to regulations and restrictions on digital trade. According to the OECD database, the digital services trade restrictiveness index of ASEAN members indicates a relatively open to foreign digital services (Table 4). However, for sector-specific restrictiveness, the services trade restrictiveness index for accounting in Thailand and legal in Indonesia is close to one, indicating they are almost entirely closed to foreign service providers (Table 5). Aligned with the findings of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and Google (2022), the regulatory environment and challenges in logistics act as significant barriers to exports, with half of MSME owners identifying foreign and domestic regulations, along with delays and high logistics costs related to customs clearance, as the primary obstacles to exporting.

| Economy | 2014 | 2022 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 0.232 | 0.232 |

| Cambodia | 0.404 | 0.405 |

| Indonesia | 0.307 | 0.307 |

| Lao PDR | 0.523 | 0.499 |

| Malaysia | 0.127 | 0.127 |

| Philippines | 0.127 | 0.127 |

| Singapore | 0.203 | 0.200 |

| Thailand | 0.141 | 0.141 |

| Viet Nam | 0.106 | 0.146 |

| Economy | Logistics cargo-handling | Logistics storage and warehouse | Logistics freight forwarding | Logistics customs brokerage | Accounting | Legal |

| Indonesia | 0.424 | 0.362 | 0.325 | 0.290 | 0.698 | 0.920 |

| Malaysia | 0.256 | 0.230 | 0.252 | 0.255 | 0.283 | 0.653 |

| Singapore | 0.285 | 0.292 | 0.282 | 0.239 | 0.203 | 0.325 |

| Thailand | 0.428 | 0.472 | 0.385 | 0.378 | 1.000 | 0.580 |

| Viet Nam | 0.427 | 0.303 | 0.264 | 0.268 | 0.251 | 0.569 |

Growing concerns regarding data privacy and security, among other factors, have prompted calls for more extensive and comprehensive regulation of the Internet and its underlying data transfers. Governments are updating their data-related rules and implementing two measures: limitations on cross-border data transfers, primarily to safeguard privacy, and requirements for local data storage, either for audit purposes or to protect privacy (OECD 2019). Restrictions on data transfers can have significant trade implications when they impact the movement of data, which is essential for global value chain coordination or for MSMEs to engage in trade.

Existing Policy

At the regional level, ASEAN has concluded various agreements and policies to promote the digital economy and cross-border transactions. The ASEAN Digital Integration Framework and its Action Plan serve as a comprehensive blueprint for digital integration efforts, covering trade facilitation, data flows, electronic payments, entrepreneurship, and talent. Furthermore, the Bandar Seri Begawan Roadmap, issued in 2021, focuses on accelerating ASEAN’s economic recovery and digital economy integration in response to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the Masterplan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025 recognizes the importance of backbone infrastructure, regulatory frameworks for new digital services, sharing best practices on open data, and equipping MSMEs with the necessary capabilities to leverage new technologies and enhance digital connectivity (ASEAN Secretariat 2016).

The ASEAN Data Management Framework and Model of Contractual Clauses for Cross-Border Data Flows are crucial in digital data governance. The Data Management Framework guides businesses in establishing effective data management systems that include data governance structures and safeguards. In contrast, the Model of Contractual Clauses offers standardized contractual terms and conditions that can be integrated into legally binding agreements when businesses transfer personal data across borders. These clauses streamline negotiations, reduce compliance costs and time that particularly benefit small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and ensure personal data protection during cross-border transfers. Moreover, the ASEAN framework on Digital Data Governance, adopted in 2017, establishes regulatory guidelines to facilitate the free flow of data within the region while upholding necessary data protections during transfers, encouraging a dynamic data ecosystem.

The ASEAN Work Programme on Electronic Commerce addresses various aspects of digital trade, including consumer protection, the security of electronic transactions, and payment systems. It focuses on essential areas such as trade facilitation, education and technology competency, electronic payment and settlement, online consumer protection, cybersecurity, and logistics to enhance e-commerce. Moreover, the ASEAN Digital Masterplan 2025 offers a comprehensive roadmap for ASEAN member states to improve their citizens’ participation in the digital economy, highlight the importance of developing advanced digital skills as a critical intervention, and set a direction to achieve digital inclusivity within the ASEAN community by improving access to digital technologies for people across the region (ASEAN Secretariat 2021a).

Regarding trade facilitation, the ASEAN Single Window (ASW) is a regional platform enabling the electronic exchange of shipment information among the 10 Southeast Asian countries. The ASW integrates the National Single Windows of ASEAN member states, promoting seamless data exchange between them. However, the full adoption of the ASEAN Customs Declaration Document (ACDD), an electronic document facilitating the exchange of export declaration information between member states, is yet to be achieved by all countries. Utilizing the ACDD could reduce clearance time for import consignments. However, it is an optional system for traders exporting goods to ASEAN member states ready for exchange, including Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. A recent trade facilitation initiative is the Initiative for ASEAN Integration Work Plan IV (ASEAN Secretariat 2020a), which aims to enhance standards harmonization, facilitate trade, and promote e-commerce within ASEAN. It focuses on implementing trade facilitation measures, improving technical capacity, and strengthening legal frameworks for e-commerce.

At the country level, ASEAN member states have different policy priorities for the digital economy and cross-border transactions, according to the International Trade Administration. For instance, Thailand focuses on digital infrastructure with the Thailand Industry 4.0 policies (Kohpaiboon 2020), including constructing a broadband network for all villages. Singapore emphasizes digital economy agreements to support businesses, particularly SMEs, in digital trade. Indonesia prioritizes digital infrastructure to enhance internet access, promoting digital government such as through the e-government system (Sistem Pemerintahan Berbasis Elektronik) and empowering digital skills through various initiatives, for example, the National Movement on Digital Literacy and the Digital Talent Scholarship program. Digital cross-border transactions are also regulated by the Minister of Trade Regulation No. 50/2020, which covers requirements for business licenses and the appointment of Indonesian representatives by foreign e-commerce businesses.

Recommendations

Promoting data sharing with adequate protection and security measures. To achieve this, one effective approach might be adopting a data transfer mechanism such as the standard contract clauses used in the EU as a reliable legal platform for regional data sharing under the existing ASEAN policies on digital data governance. The data transfer mechanism might summarize sets of contractual responsibilities and conditions to ensure that the transferred data receives the same level of protection as required by the regulations. By utilizing standardized templates, this mechanism streamlines the agreement process rapidly and more efficient for specific data flows. Hence, building trust and commitment among ASEAN member state governments is crucial for enabling data sharing.

Streamlining regulations governing the adoption of new technologies in digital payment systems in response to the evolving digital industry landscape. Considering certain ASEAN members have not implemented common digital payment systems such as the QR payment, implementing harmonized digital payment system regulations at the regional level across ASEAN member countries might be a practical strategy to embody the action while ensuring a coherent method to manage digital payment and transaction innovations.

Offering guidance to MSMEs on leveraging digital tools and technologies for exports. Addressing the knowledge gap within the MSME community by providing tailored support can enhance their skills and capabilities. Enhancing digital literacy and upskilling programs for the younger generation to meet the demands of employers and prepare citizens and businesses for the rapidly evolving digital landscape. Collaborating with the private sector to design relevant digital skills roadmaps and accelerating their implementation in prioritized sectors is essential.

References

Asian Development Bank (ADB). 2023 ASEAN and Global Value Chains: Locking in Resilience and Sustainability. Manila: ADB.

ASEAN Secretariat. 2016. Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025. Jakarta: ASEAN.

_____. 2020a. Initiative for ASEAN Integration (IAI) Work Plan IV (2021-2025). Jakarta: ASEAN.

_____. 2020b. Report on Promoting Sustainable Finance in ASEAN. Jakarta: ASEAN.

_____. 2020c. ASEAN State of Climate Change Report. Jakarta: ASEAN.

_____. 2021a. ASEAN Digital Integration Index Report 2021. Jakarta: ASEAN.

Beschorner, N. 2021. The Digital Economy in Southeast Asia: Emerging Policy Priorities and Opportunities for Regional Collaboration. In C. Findlay and S. Tangkitvanich, eds. New Dimensions of Connectivity in the Asia-Pacific. Canberra: ANU Press, pp. 121–156.

Box, S., and J. Lopez-Gonzalez. 2017. The Future of Technology: Opportunities for ASEAN in the Digital Economy. In S. Tay and J. Tijaja, eds. Global Megatrends: Implications for the ASEAN Economic Community. Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, pp. 37–60.

Chen, L. and L. Ruddy. 2020. Improving Digital Connectivity: Policy Priority for ASEAN Digital Transformation. ERIA Policy Brief7. Jakarta: Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

González, L. 2019. Fostering Participation in Digital Trade for ASEAN MSMEs. OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 230.

Google, Temasek and Bain & Company. 2019. e-Conomy SEA 2019 Report. 3 October. https://www.bain.com/insights/e-conomy-sea-2019/ (accessed 17 May 2023).

_____. 2022. e-Conomy SEA 2022: Through the Waves, Towards a Sea of Opportunity. 27 October. https://economysea.withgoogle.com. (accessed 15 May 2023).

Hoppe, F., T. May, and J. Lin. 2018. Advancing Towards ASEAN Digital Integration, Empowering SMEs to Build ASEAN’s Digital Future. Bain & Company. 3 September. https://www.bain.com/insights/advancing-towards-asean-digital-integration/ (accessed 15 May 2023).

International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and Google. 2022. MSME Digital Exports in Southeast Asia – A Study of MSME Digital Exports in 10 ASEAN Markets. 17 November. https://iccwbo.org/news-publications/policies-reports/msme-digital-exports-in-southeast-asia-a-study-of-msme-digital-exports-in-10-asean-markets/#single-hero-document (accessed 15 May 2023).

Kohpaiboon, A. 2020. Industry 4.0 Policies in Thailand. ISEAS Economics Working Paper No. 2020–02. Singapore: ISEAS.

Lee, C. 2021. Digital Trade in Southeast Asia: Measurements and Policy Directions. ISEAS Perspective No. 147. Singapore: ISEAS.

OECD, World Trade Organization (WTO), and International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2020. Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade Version 1. https://www.oecd.org/sdd/its/Handbook-on-Measuring-Digital-Trade.htm (accessed 4 May 2023).

Statista. 2023. Global Social Network Penetration Rate as of January 2023, by Region. Statista. 14 February. https://www.statista.com/statistics/269615/social-network-penetration-by-region/ (accessed 15 May 2023).

Tan, M. 2022. Realizing the Potential of Over 71 Million MSMEs in Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia Development Solutions. 14 March. https://seads.adb.org/solutions/realizing-potential-over-71-million-msmes-southeast-asia (accessed 14 May 2023).

Tong, S., Y. Li, and T. Kong. 2021. Exploring Digital Economic Agreements to Promote Digital Connectivity in ASEAN. ERIA Working Papers DP-2021-24. Jakarta: Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2022. Digital Trade: Opportunities and Actions for Developing Countries. UNCTAD Policy Brief No. 92.

Wagner. J. 2012. International Trade and Firm Performance: a Survey of Empirical Studies Since 2006. Review of World Economics 148(2): 235–267.

World Economic Forum (WEF). 2021. ASEAN Digital Generation Report: Pathway to ASEAN’s Inclusive Digital Transformation and Recovery. 13 October. https://www.weforum.org/reports/asean-digital-generation-report-pathway-to-asean-s-inclusive-digital-transformation-and-recovery/ (accessed 15 May 2023).