The lowering purchasing power and the declining middle-income class have recently become rising economic issues in Indonesia. The lower purchasing power is concerning as, according to Statistics Indonesia (Badan Pusat Statistik, BPS) data, more than half of the Indonesian macroeconomic condition is attributed to household consumption, while the middle class has become the backbone of the economy, and hence, a reduction in the middle class would pose a considerable issue to the economic growth and development. However, one might perceive this phenomenon as an anomaly as macroeconomic indicators exhibit relative stability. While macroeconomic figures lead certain parties to translate the economy as doing well, structural issues might hide behind the seemingly stable Indonesian economic state.

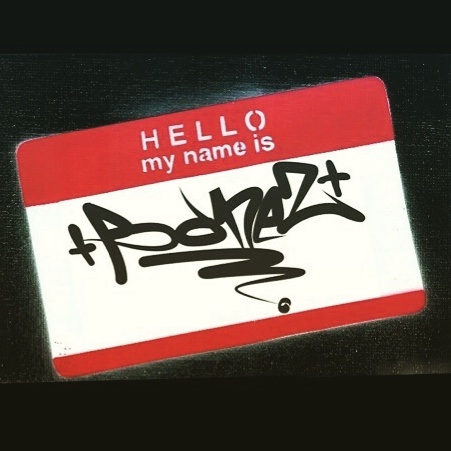

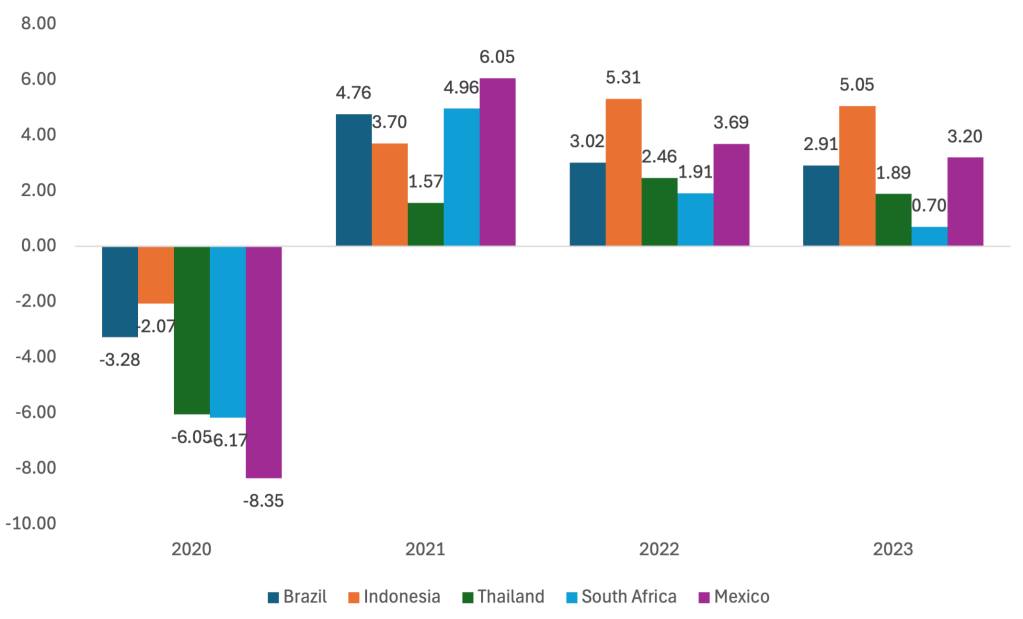

At a glance, Indonesian macroeconomic indicators appear to be performing relatively well. For instance, Indonesia recorded an economic growth of 5.02 percent in 2024, higher than other developing economies like Brazil (3.6 percent), Thailand (3.2 percent), South Africa (0.9 percent), and Mexico (0.5 percent), according to Trading Economics. After the pandemic, Indonesia has also enjoyed relatively increasing and stable economic growth, gradually recovering from the pandemic in 2020 that hit economic growth to a level of -2.07 percent, according to World Bank data (Figure 1). Furthermore, the unemployment rate also shows a seemingly desirable performance with a declining trend from 4.26 percent of the total labor force in 2020 to 3.31 percent in 2023 (Figure 2).

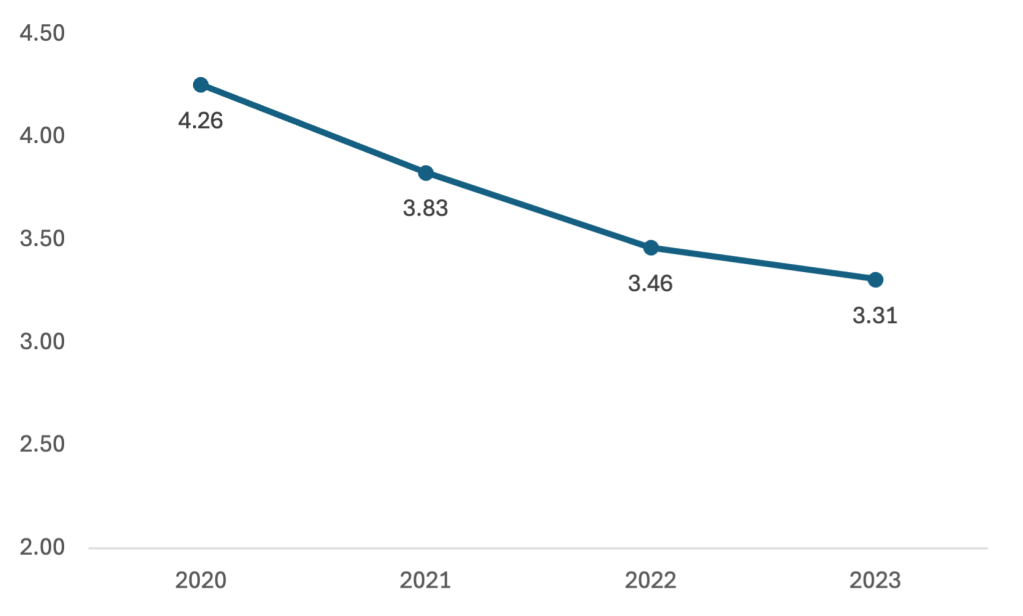

Nonetheless, economic issues at a more micro level were raised due to two significant phenomena: the reduced middle-income class and lower purchasing power. The middle-income class has been decreasing while the income inequality has worsened. There has been a notable decline of 4.2 percentage points in the Indonesian middle class from 23 percent in 2018 to 18.8 percent in 2023, while the share of the vulnerable and the aspiring middle class has risen by 1.4 and 3.8 percentage points, respectively (Figure 3).

National Socioeconomic Survey (Susenas)

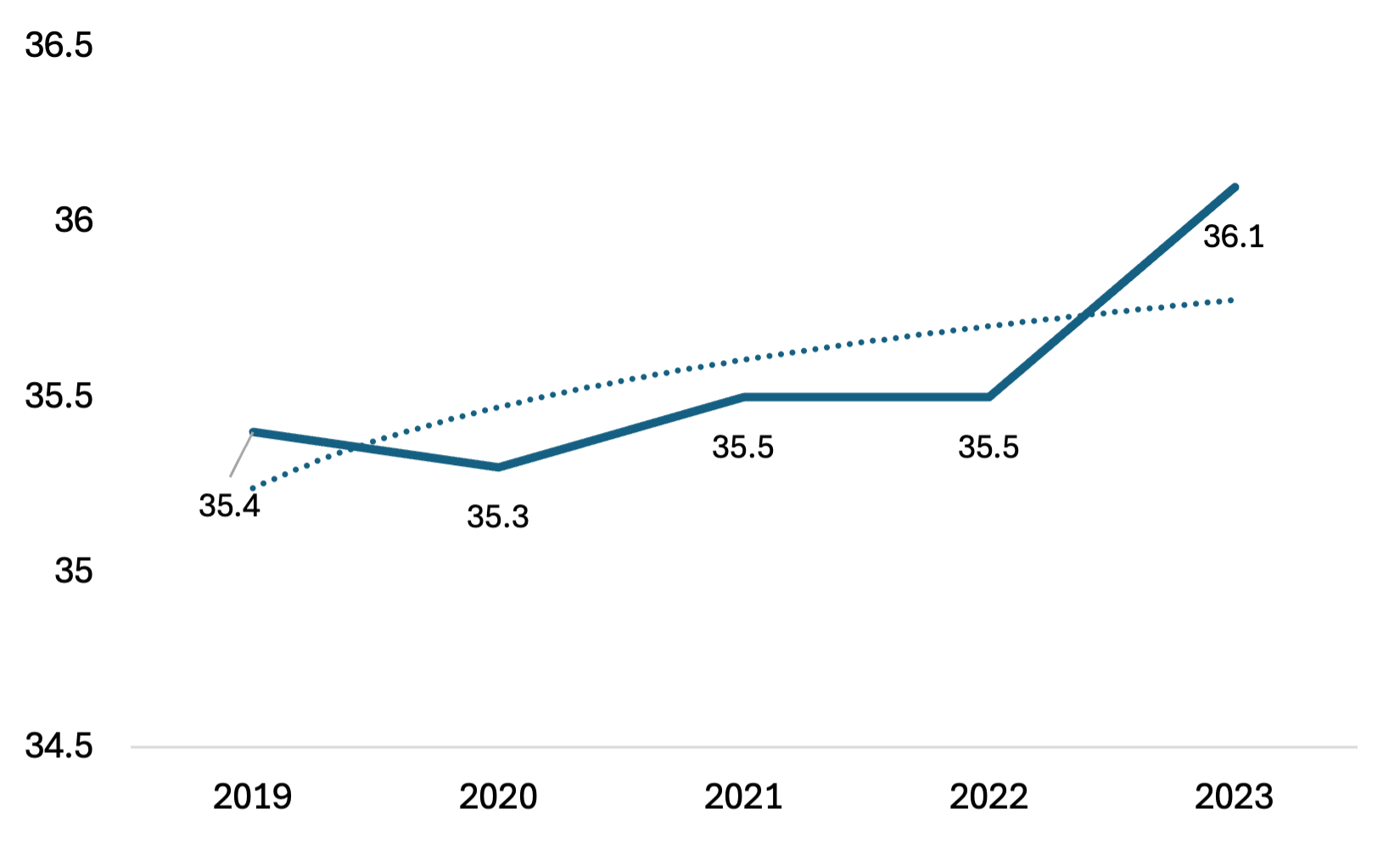

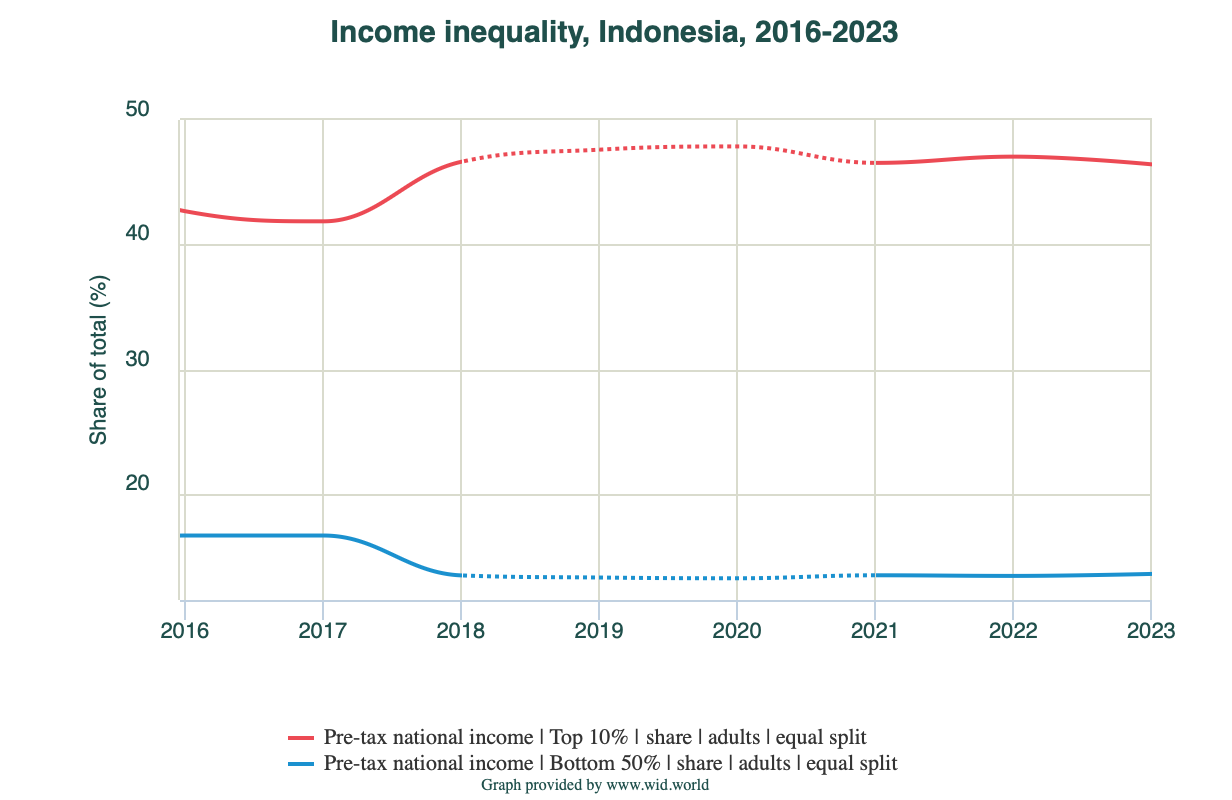

On the other hand, the economic growth might have been unevenly distributed. To illustrate, indicators of income inequality indicate a higher gap in income distribution, such as the widening gap of share of the total national income between the top 10 percent and bottom 50 percent of individuals’ income (right panel in Figure 4) and the increasing trend in the Gini coefficient (left panel in Figure 4), indicating a rising income inequality and uneven redistribution of economic growth and corroborating the argument of declining middle class.

Figure 4. Indonesian Gini Coefficient (left) and Income Inequality (right). Source: World Development Indicators, World Inequality Database.

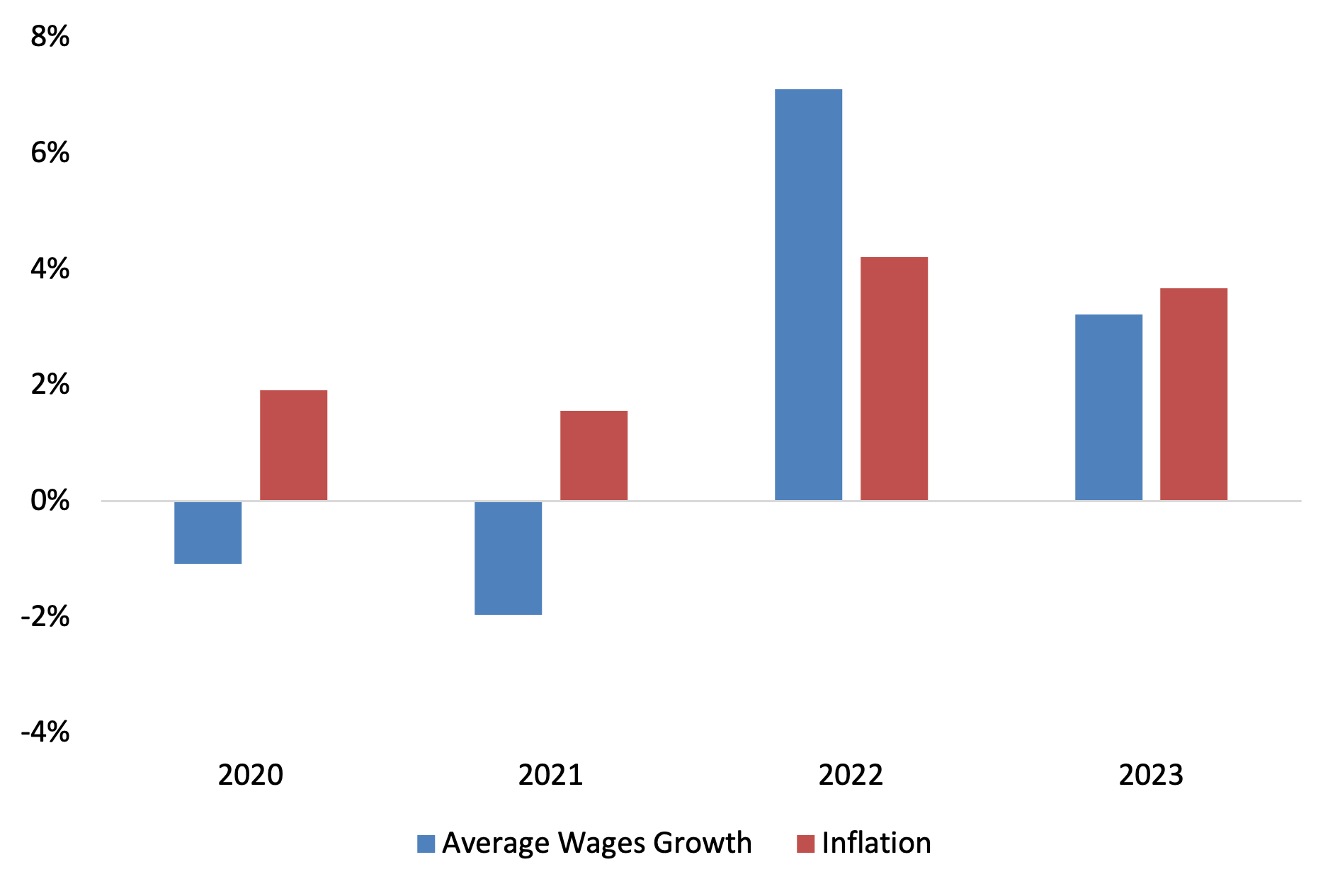

The reduced purchasing power has been raised by many by citing several recent and contemporary indicators within the last year, including the decline in value-added tax, lower consumption growth rate and retail and durable goods sales, lower propensity to saving, and lower level of inflation and deflation happening in the country, which reflects the changes in the short term and hence are translated by some as an anomaly. However, the reduced purchasing power might have resulted from a fundamental and more structural issue in the economy. According to the theory, purchasing power can be reflected by the ratio of wages to price level (P), reflecting the purchasing power of individuals’ earnings ((W/P). This implies that when the price level increases (inflation rate) higher than wage growth, individuals’ purchasing power will erode. Figure 5 indicates that the inflation rate in 2020, 2021, and 2023 was substantially larger than the growth in average wages, which might be attributed to the lowered purchasing power.

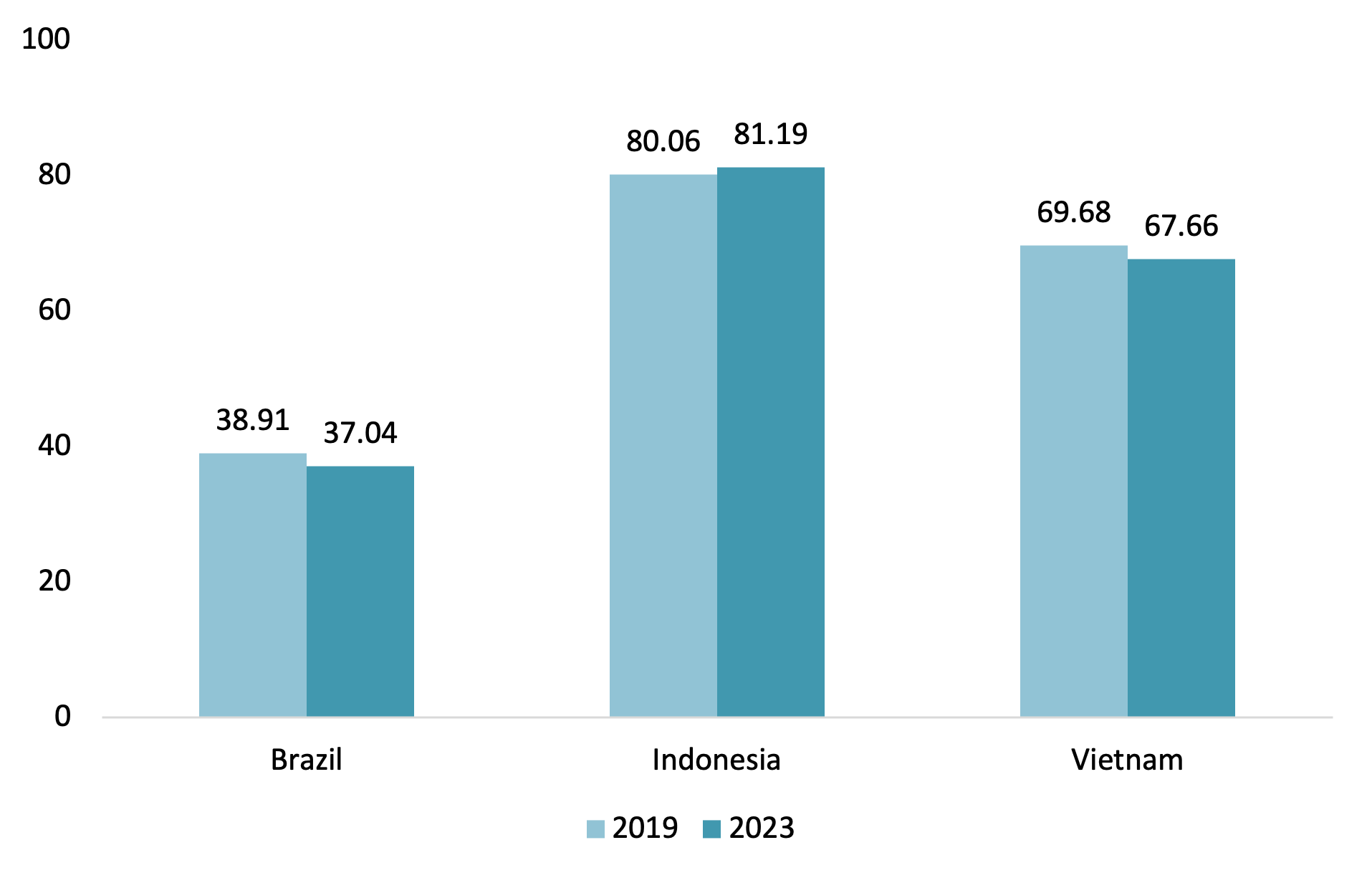

Moreover, the structural issue behind the lower purchasing power could occur even when the unemployment rate has declined. One possible reason might be attributed to the labor force shift from the formal to the informal sector. Statistics Indonesia through Sakernas recorded a substantial growth of approximately 2.5 times in the net new jobs in the informal sector in 2018-2023 relative to the previous period of 2013-2018, while new jobs in the formal sector were degraded considerably by 63.14 percent. Meanwhile, compared to other developing economies like Brazil and Vietnam, Indonesia not only has a larger portion of informal sector employment but also exhibits positive growth in 2023 compared to the rate in 2019 before the pandemic (Figure 6). Informality might be a considerable issue as informal firms operate entirely outside the formal economy, conducting all transactions in cash—whether hiring workers, purchasing inputs, or selling products. They remain persistently informal, exhibit extremely low productivity, and gain little from transitioning to formal status (La Porta & Shleifer, 2014).

What Could be Done?

Given the structural issues affecting consumers’ purchasing power and the middle class in Indonesia, mitigating interventions are inevitable. In the short term, support for the consumers, particularly for the middle class such as through electricity tariff discounts, might be effective in improving their purchasing power while ensuring the reallocation of the government budget cut that has been undergone to sectors that produce significant multiplier effects to the economy, such as sustainable employment creation in the formal sector.

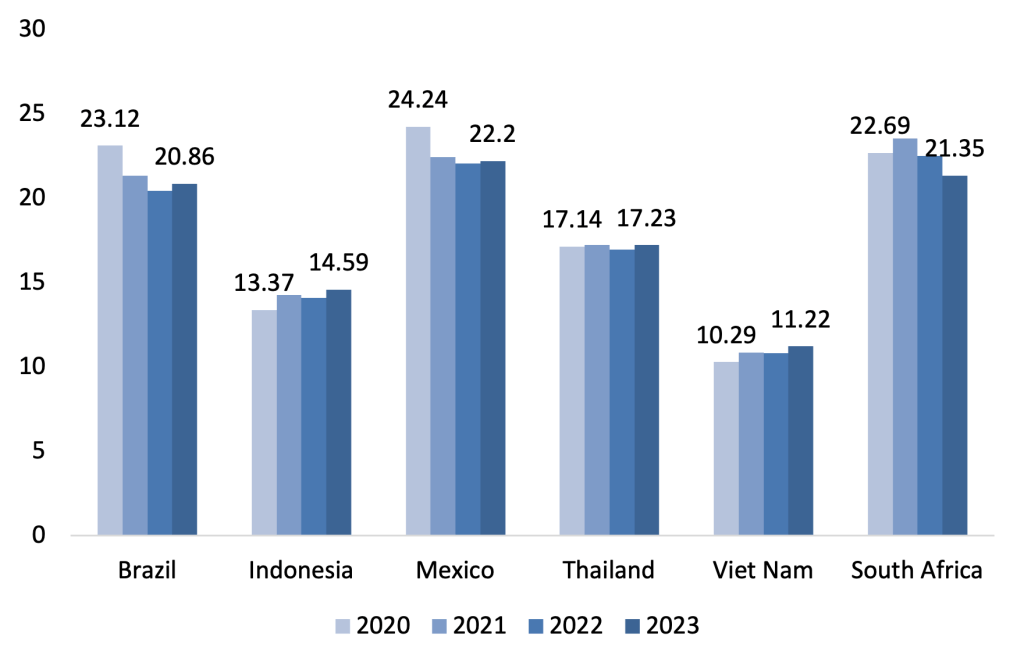

The more strategic approaches might require attracting foreign investment to achieve higher economic growth, restore purchasing power, and strengthen the middle class through formal employment creation. The approaches would be taken in the medium to longer term, targeting primarily two objectives: productivity and institutions. Productivity is related to competitiveness, and these variables substantially influence the consideration of foreign investors to invest in an economy. Nonetheless, several indicators of productivity of production factors in Indonesia indicate the need for improvement. First, labor productivity in Indonesia is relatively lower than tantamount to developing economies (Figure 7), but opportunity rises as the trend is positively growing. Accordingly, labor productivity should be enhanced through education and training, innovation and research and development encouragement, and competitive and high-value industries fostering to make Indonesia more competitive, which would eventually contribute to higher economic growth.

Second, Indonesian capital investment is arguably inefficient, as indicated by the incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR) of 6.33 in 2023, meaning that an additional capital investment of 6.33 percent is needed to produce a 1 percent economic growth. It is worth noting that a higher ICOR reflects that more investment is needed to produce the same growth level, indicating higher inefficiency. Indonesia’s ICOR was higher than the ideal ICOR (between 3 and 4) and also higher compared to ASEAN members, including the Philippines (3.7), Thailand (4.4), Malaysia (4.5), and Vietnam (4.6). Therefore, to attract more investment, Indonesia should improve its efficiency by enhancing productivity, adopting new technologies and digitalization, optimizing investment allocation, and reducing capital waste.

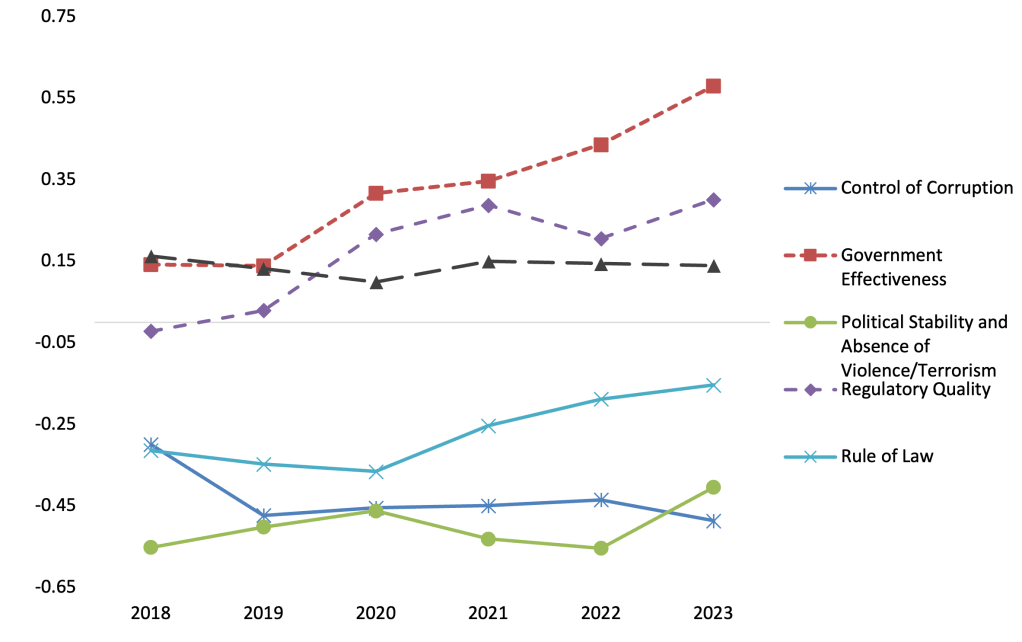

Additionally, Indonesia needs to reform its institutions to improve institutional quality, particularly in the rule of law, control of corruption, and political stability. Figure 8 shows governance aspects in Indonesia, indicating that there has been better improvement in the quality of public services, the capacity of the civil service and its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, regulatory quality, and public participation. However, Indonesia is still lagging in economic agents’ confidence in the rules of society, control of corruption practices and political stability, and absence of violence.

Meanwhile, institutional quality attracts foreign direct investment inflows (Khan et al., 2023), is associated with lower inequality and higher economic growth and human development levels, and helps manage the benefits of commodity exports while mitigating the developmental costs of commodities export dependence (Natanael, 2024). Therefore, institutional reform could be targeted at a more stable rule of law to enhance confidence in and abide by the rules of society, the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence, improved corruption control and political stability through reliable and society-oriented regulations and policies.

In conclusion, although some Indonesian macroeconomic indicators, such as economic growth and the unemployment rate, suggest a relatively stable performance, they might not necessarily be the entire picture of the economy. The structural issues might be overlooked behind the recent reduced number of middle-class and lower purchasing power phenomena, including the increasing informality and stagnated wages. Thus, several actions might be urgently needed to resolve the issues, particularly in the medium to longer term, such as improving labor productivity and investment efficiency as well as enhancing institutional quality in the rule of law, control of corruption, and political stability.

References

Khan, H., Dong, Y., Bibi, R., & Khan, I. (2023). Institutional quality and foreign direct investment: Global evidence. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 1-45.

La Porta, R., & Shleifer, A. (2014). Informality and development. Journal of economic perspectives, 28(3), 109-126.

Natanael, Y. (2024). Is Less Commodity Dependence Better for Economic Equality, Economic Growth, and Human Development?. Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies, 09749101241300637.